Preventing ESL by enhancing resiliency

Thursday 23 July 2015, by

Educational resilience is related to staying in school despite high risks (e.g. low social economic status, migrant status) present in one’s life and, as such, can offer a path for preventing ESL. Enhancing educational resilience is a result of fostering protective factor(s) on either the contextual (family, school, community, e.g. parental education trainings, positive school climate improvements…) or individual level (e.g. mind-set trainings).

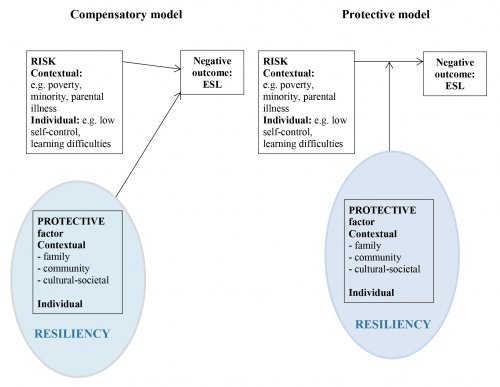

Resilience entails positive adaptation, e.g. doing well despite high risks or adversities. These adversities are either contextual (e.g. poverty, minority status, immigrant status, parental illness, harsh parenting…) or individual (e.g. illness, self-control impairment, learning difficulties, lack of coping skills…). Two models of resilience can be used for prevention and intervention planning: protective (a protective factor moderates the effect of a risk factor) and compensatory (a protective factor tempers a risk factor). The first one supports indicative prevention and the second universal prevention. Educational resilience is defined in terms of educational success even though there are personal attributes and environmental circumstances which reduce the likelihood of succeeding (Sacker & Schoon, 2007). Since the mentioned adversities are also related to ESL, the resilience concept can contribute significantly to understanding and preventing ESL by providing an answer to why some students stay in school even though high risks for ESL are present in their lives. The difference between individuals who are found to be more resilient than others in the face of adverse circumstances is the number of protective factors: resources (positive contextual factors) and individual assets (positive individual characteristics) found in one’s environment (Masten, 2016). The protective factors can be grouped in four categories: child characteristics, family characteristics, community characteristics, and cultural or societal characteristics. Based on a review of possible protective factors, certain practical implications of enhancing resilience are listed on the contextual level (e.g. family, school and community; such as parental education trainings, positive school climate improvement, bettering student-teacher relations) and individual level (e.g. focusing on mind-set intervention, boosting social and emotional skills, self-regulation techniques). In the conclusion, the importance of enhancing any of the protective factors is stressed – even a single protective factor can make a great difference to the life of a young person and prevent ESL.

Abubakar, A., & Dimitrova, R. (2016). Social connectedness, life satisfaction and school engagement: Moderating role of ethnic minority status on resilience processes of Roma youth. European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 13(3), 361–371.

Ahmavaara, A., & Houston, D. M. (2007). The effects of selective schooling and self-concept on adolescents’ academic aspiration: An examination of Dweck’s self-theory. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 77, 613–632.

Blackwell, L., Trzesniewski, K., & Dweck, C. S. (2007). Implicit theories of intelligence predict achievement across an adolescent transition: A longitudinal study and an intervention. Child Development, 78, 246–263.

Borge, A. I., Motti-Stefanidi, F., & Masten, A. S. (2016). Resilience in developing systems: The promise of integrated approaches for understanding and facilitating positive adaptation to adversity in individuals and their families. European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 13(3), 293–296.

Cadima, J., Enrico, M., Ferreira, T., Verschueren, K., Leal, T., & Matos, P. M. (2016). Self-regulation in early childhood: The interplay between family risk, temperament and teacher–child interactions. European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 341–361.

Claro, S., Paunesku, D., & Dweck, C. S. (2016). Growth mindset tempers the effects of poverty on academic achievement. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 113, 8664−8668.

Doll, B. (2013). Enhancing resilience in classrooms. In S. Goldstein, & R. B. Brooks (Eds.), Handbook of resilience in children (399–411). New York: Springer.

Dweck, C. (2008). Can personality be changed? The role of beliefs in personality and change. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 17, 391–394.

Dweck, C. (2012). Mindsets and human nature: Promoting change in the Middle East, the schoolyard, the racial divide, and willpower. American Psychologist, 67, 614–622.

Dweck, C. S. (2006). Mindset. New York, NY: Random House.

Felner, R. D., & DeVries, M. (2013). Poverty in childhood and adolescence: A transactional-ecological approach to understand and enhancing resilience in contexts of disadvantage and developmental risk. In S. Goldstein, & R. B. Brooks (Eds.), Handbook of resilience in children (105–127). New York: Springer.

Good, C., Aronson, J., & Inzlicht, M. (2003). Improving adolescents’ standardized test performance: An intervention to reduce the effects of stereotype threat. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 24, 645– 662.

Grolnick, W. S., Friendly, R. W., & Bellas, V. M. (2009). Parenting and children’s motivation at school. In K. R. Wenzel, & A. Wigfield, Handbook of motivation in school (279–300). New York: Routledge.

Hupfeld, K. (2007). Resiliency skills and dropout prevention: A review of the literature. Denver, CO: ScholarCentric.

Jackson, S., & Martin, E. Y. (1998). Surviving the care system: Education and resilience. Journal of Adolescence, 21, 569–583.

Jaffe, R. S. (2013). Family violence and parent psychopathology: Implications for children’s socioemotional development and resilience. In S. Goldstein, & R. B. Brooks (Eds.), Handbook of resilience in children (127–143). New York: Springer.

Kaplan, H. B. (2013). Reconceptualizing resilience. In S. Goldstein, & R. B. Brooks (Eds.), Handbook of resilience in children (39–57). New York: Springer.

Kuperminc, G. P., Wilkins, N. J., Roche, C., & Alvarez-Jimenez, A. (2009). Risk, resilience, and positive development among Latino youth. In F. A. Villarruel, G. Carlo, J. M. Grau, M. Azmitia, N. J. Cabrera, & T. J. Chahin (Eds.), Handbook of US Latino psychology: Developmental and community-based perspectives (213–233). Hoboken: Sage.

Luthar, S. S. (1993). Methodological and conceptual issues in research on childhood resilience. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 34(4), 441–453.

Masten, A. S. (1994). Resilience in individual development: Successful adaptation despite risk and adversity. In M. Wang, & E. Gordon (Eds.), Educational resilience in inner city America: Challenges and prospects. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Masten, A. S. (2007). Resilience in developing systems: Progress and promise as the fourth wave rises. Development and Psychopathology, 19(3), 921–930.

Masten, A. S. (2011). Resilience in children threatened by extreme adversity: Frameworks for research, practice, and translational synergy. Development and Psychopathology, 23(2), 493–506.

Masten, A. S. (2016). Resilience in developing systems: The promise of integrated approaches. European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 13(3), 279–313.

Masten, A. S., Cutuli, J. J., Herbers, J. E., & Reed, M. G. (2009). Resilience in development. In S. J. Lopey & C. R. Snyder (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of positive psychology (117–133). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Masten, A. S., Cutuli, J. J., Herbers, J. E., Hinz, E., Obradović, J., & Wenzel, A. J. (2014). Academic risk and resilience in the context of homelessness. Child Development Perspectives, 8, 201–206.

Motti-Stefanidi, F. (2015). Risks and resilience in immigrant youth adaptation: Who succeeds in the Greek school context and why? European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 12(3), 261–274.

O’Rourke, E., Haimovitz, K., Ballwebber, C., Dweck, C. S., & Popović, Z. (2014). Brain points: A growth mindset incentive structure boosts persistence in an educational game. In CHI’14: Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (3339–3348). New York, NY: Association for Computing Machinery.

Ostaszewski, K. (2012). Resilience: Compensatory, Protective, and Promotive Factors for Early Substance Use. 1st Annual Workshop: Lifespan Development of Substance Abuse, Kiev, Ukraine, November, 14–17.

Paunesku, D., Walton, G. M., Romero, C., Smith, E. N., Yeager, D. S., & Dweck, C. S. (2015). Mind-set interventions are a scalable treatment for academic underachievement. Psychological Science, 26, 784–793.

Sacher, A., & Schoon, I. (2007). Educational resilience in later life: Resources and assets in adolescence and return to education after leaving school at age 16. Social Science Research, 36, 873–896.

Sandler, I., Ingram, A., Wolchik, S., Tein, J. Y., & Winslow, E. (2015). Long-term effects of parenting focused preventive interventions to promote resilience of children and adolescents. Child Development Perspectives, 9(3), 164–171.

Schoon, I., (2006). Risk and resilience. Adaptations in changing times. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Sheridan, S. M., Sjuts, T. M., & Coutts, M. J. (2013). Understanding and promoting the development of resilience in families. In S. Goldstein, & R. B. Brooks (Eds.), Handbook of resilience in children (143–161). New York: Springer.

Turner, M. Y., Thurston, D. A., Gaye, Z., & Gentry, L. (2008). The relationship of risk, resilience, and dropout: Implications for urban youth living in the south. Conference Proceedings, 646–672. Scarborough: National Association of African American Studies.

Walsh, F. (2016). Family resilience: A developmental systems framework. European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 13(3), 313–325.

Wenzel, K. R. (2009). Students’ relationship with teachers as motivational contexts. In K. R. Wenzel, & A. Wigfield, Handbook of motivation in school (303–348). New York: Routledge.

Yeager, D. S., & Dweck, C. S. (2012). Mindsets that promote resilience: When students believe that personal characteristics can be developed. Educational Psychologist, 47, 302−314.

Yeager, D. S., Johnson, R., Spitzer, B., Trzesniewski, K., Powers, J., & Dweck, C. S. (2014). The far-reaching effects of believing people can change: Implicit theories of personality shape stress, health, and achievement during adolescence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 106, 867–884.

Zins, J. E., Weissberg, R. P., Wang, M. C., & Walberg, H. J. (Eds.). (2004). Building academic success on social and emotional learning: What does the research say? New York: Teachers College Press.